It is amazing to see how resilient nature can be. Over the course of the centuries, many animals have been able to adapt to habitats created by humans, with the disappearance of natural landscapes and the emergence of villages and cities. Consider, for example, the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus). Originally, this bird of prey breeds in niches or on ledges of rock walls. Of course, the bird still does that, for example in the Belgian Ardennes and in old quarries. However, when the bird expanded its habitat, it found cities with high buildings in the Netherlands, among other places. These structures kind of resemble its natural rocky habitat. These cities come with good hunting grounds and nests could be built on the ledges of those tall buildings. The peregrine falcon is not the only one who takes advantage of our buildings to build a nest. The house martin (Delichon urbicum), for example, is also originally a cliff-nesting bird that has been nesting in villages and towns for centuries. Unfortunately, they are all too often deprived of this opportunity, because people do not want “clutter” at their house.

Cockles and mussels

Another bird that increasingly seeks its breeding grounds in the vicinity of humans is the Eurasian oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus). A very recognizable wader, you’ve probably seen one before. It cannot be missed with its black and white plumage, red beady eyes and bright orange-red bill. A bird that nowadays occurs throughout our country, except in forest areas and small-scale cultural landscape. It really is a bird of the open ground. Not surprising, because it is originally a coastal bird. That explains its Dutch name: Scholekster, which literally means ‘plaice magpie’. So you would think that this bird fancies to eat plaice (‘schol’) (Pleuronectes platessa), but it doesn’t eat fish at all. Its coastal menu includes shellfish such as cockles and mussels, as well as shrimp and crabs. But no plaice. So where does the Dutch name come from?

Onomatopoeia?

The second part magpie in its Dutch name, ekster, comes from the resemblance (in terms of colour) with the magpie (Pica pica). Although from a distance the magpie appears to have a black and white plumage, but when the sun shines on the feathers, beautiful greens and blues emerge due to the iridescent effect. The plumage of the oystercatcher does not show this effect. There are various explanations for the origin of plaice in the name, ranging from a split shell part to an onomatopoeia (sound imitation). There are also ideas that plaice comes from the Early New Dutch word for clod. The true origin has not yet been traced, but it is clear that the name has nothing to do with the fish species plaice.

Oysterfisher

The confusion is even greater because the English call it oystercatcher and the French preneur d’huitres, which means the same. And the Germans call it an Austernfischer, which means oysterfisher. And this name is also reflected in the scientific name of the bird. The genus name has nothing to do with catching oysters, but everything to do with the colour of its legs. Haematopus comes from the Greek haima (= blood) and pous (= leg), which refers to red legs. A name that is not quite right, since the oystercatcher’s legs are pink. The species name ostralegus means as much as oyster collector. So once again those oysters, while the bird doesn’t eat oysters at all. It can still open a mussel or cockle with its beak but it’s unable to open an oyster. The bird does however have a close relative that lives on the coasts of North and South America and that bird does eat oysters: the American oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus). In fact, oysters are the staple of the menu for this species. At first glance, both birds look identical.

Linnaeus

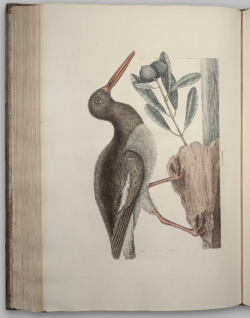

The English naturalist, draftsman and explorer Mark Catesby (1682 – 1749) encountered the bird on one of his travels through the Americas and draws and describes it in volume 1 of his Natural History of Carolina (1730-1732). See the images on the left and right. Not knowing that the American bird is not the same as the species that occurs in Europe and Asia, this bird is given the name oystercatcher upon Catesby’s return to England. Linnaeus adopted this for the species name in 1758 and the Eurasian bird has since also been scientifically named as an oystercatcher.

Customize menu

no images were found

To come back to the opening of this blog. The adaptability of animals, because that’s what this blog was about. The oystercatcher is, as I wrote, originally a bird of the coast. The increasing building on the coast, beach tourism and the decline in food from the coastal bed, among other things, have ensured that the bird increasingly resides inland, especially in polder areas with arable and pasture land. There you can encounter them in groups, often among lapwings (Vanellus vanellus) and black-tailed godwits (Limosa limosa). It has had to adjust its menu a bit, because one will not easily find cockles and mussels in those areas. There the bird mainly feeds on worms, crane-fly larvae and other invertebrates that live in the ground. The inland breeding habitat of the oystercatcher comprises wet, herb-rich grassland, in short grazed meadows and on arable land. Incidentally, the ‘domestic’ oystercatchers have evolved over the years in such a way that their beaks have also adapted to the changed food pattern. See the image opposite and this article in Dutch on the CHIRP (Cumulative Human Impact on biRd Populations) website.Sixty percent decrease

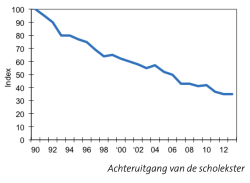

Unfortunately, that was not the cure for this bird either, because since 1990 the population in the Netherlands decreased by no less than sixty percent. As with so many meadow birds, the cause of this decrease is partly due to the agricultural intensification, which meant draining wet grasslands and a large decrease in the area of herb-rich grasslands. Nowadays there is often not enough food left to raise the young. And when they do grow up, they also have a chance to end up under the mower or to fall prey to the fox (Vulpes vulpes) and ermine (Mustela erminea), among others. But those animals also need to eat. Food decreases in, for example, the Wadden area, their original habitat, also contributed to the enormous decrease in the number of birds.

Flying predators

Partly because of this, the oystercatchers have started looking for new nesting possibilities. And they found it! Nowadays many oystercatchers breed on flat roofs in cities, especially on roofs with gravel. The male makes a shallow hole in the gravel and the lady oystercatcher then lays three to four eggs in it (see the photo by Rinus Dillerop on the right). These eggs are perfectly camouflaged so they don’t stand out to predators. Although they seek refuge in the city due to predation, among other things, the danger is not completely gone of course. On the roof too they still have to be wary of flying predators. Gulls such as the herring gulls (Larus argentatus) and corvids such as carrion crows (Corvus corone) and magpies target the eggs and young chicks.

Furballs

Predation is only part of the obstacles that the oystercatchers on the roof have to overcome. Young oystercatchers are so-called nidifugous birds which means that they can explore quite quickly after they have hatched, although they are still fed by mom and dad for about four weeks. Flat roofs are often equipped with rainwater drains with a large diameter. After all, at a heavy rain quite a bit of water can fall on such a surface and it must be possible to drain it quickly. The young furballs can easily fall into such a rainwater drain while exploring the roof. Or, curious as they are, they may also get too close to the eaves. It is not without reason that the parent birds keep an eye on the young. Potential enemies are skillfully chased away with a shrill “te-pee te-pee” and feint attacks.

Hideout

Various projects have been set up to help the oystercatchers in their new habitat. Among other things, to investigate the breeding success of these new urban birds and where they get their food from. One of these studies is by Bert Dijkstra and Rinus Dillerop. Since 2008 they have been monitoring oystercatchers in the city of Assen and the surrounding area in the province of Drenthe. They do this, among other things, by mapping flat roofs where the birds nest, ringing the birds and advising the owners of the buildings on taking protective measures. For example, by installing a shelter on the roof under which the young can shelter from bad weather, sun and predators. Such a shelter can easily be created with a simple box upside down with an opening in a side or a closed pallet on the roof. A ball grid on the rainwater drainage prevents the young oystercatchers from falling in.

Nutrient-rich roadsides and grass strips

In recent years, some birds have been equipped with transmitters. As with ringing, the bird is not bothered by this. With such a transmitter it is possible to follow the movements of the birds very accurately. One can for example see where their foraging areas are located. Through these transmitters, Dijkstra and Dillerop discovered that the birds mainly get their food from road verges and strips of amenity grassland that are often found on industrial estates and not, for example, in the meadows further away. Research into the soil fauna subsequently showed that those meadows were much poorer in terms of potential oystercatcher food than those verges and strips. The combination of flat roofs and these foraging areas has turned out to be ideal for the oystercatcher. The number of breeding pairs on the roofs is on the increase, while those in the countryside are decreasing considerably. The survival of the young on the roof is also higher than the national average of 0.38 young per breeding pair per year. You can read more about the results of this research by Dijkstra and Dillerop in Assen in this article in Dutch from Drentse Vogels issue 32 from 2018.

Very old animal

And finally, a fun fact: on August 2016, an oystercatcher was observed on the Maasvlakte (industrial area created through land reclamation in the North Sea near the port of Rotterdam) by birdwatcher Hans Keijser. This bird was wearing an aluminum leg ring and by reading the number on this ring and passing it on to the Vogeltrekstation (Dutch centre for bird migration research), he found out that this bird had been ringed on 3 March 1972 (!) on the island of Texel in the Wadden Sea in the north of the Netherlands. The bird was already at least two years old at the time it was ringed, so when Hans saw the bird it had the respectable age of at least 46 years! Usually, oystercatchers don’t get older than about twenty years, so this was really an old animal.

Sources (in Dutch):

Very interesting information Theo, In the 1980’s I used to work at Philips in Groningen and where now kitchen showrooms are located there was car parking space for personnel. Between rows for cars there were gravelly kerbs, several pairs of oyster catchers nested there every year.

Thanks Lindy! Carparks with gravel are also a good spot for oystercatchers.